Perhaps no other area of ecommerce and fulfillment illustrates the challenges, complexities and opportunities than that involving home delivery of food in various forms.

The Wall Street Journal, led primarily by reporter Heather Haddon, has for some weeks now written an outstanding series of articles centered on food delivery.

I trust you will find the topic as interesting as I do, as I summarize highlights of several of those articles here today.

Gilmore Says.... |

|

Food companies are betting that such automation can reduce delivery costs by as much as 40%, according to McKinsey & Co., while also helping ease a shortage of delivery drivers. |

|

What do you say? |

|

| Click here to send us your comments |

| |

|

|

|

Most grocers and major restaurant chains are wading if not plunging into last mile delivery, in various ways, but with challenges even greater than most regular retailers are finding.

Low cost shipping puts a hit on the bottom line in an Amazon world in the food sector too. For example, last year the consultants at Cap Gemini found it costs supermarkets on average about $10 per order to deliver to a customer's residence, while they are charging around $8 per delivery.

What's worse, only 1% of almost 3000 consumers surveyed were willing to pay the full cost of grocery delivery.

Or consider restaurant chain Panera Bread, an early leader in consumer delivery. One of the Journal articles notes Panera charges $3.00 for home it delivery in most areas of the country, even though it estimates its cost per delivery (car expense, driver, special packaging) is around $5.00 – which actually sounds way too low to me.

So a customer ordering $10-12 dollars' worth of food for delivery is generating little profit or even a loss for the store. However, Panera does say that when people order home delivery, they tend to order for larger groups, so the average check is higher than it is for dine-in customers.

Still, "Billions of dollars have been spent in a quest to build services that reliably move fresh food from one place to another, yet many in the business wonder if they will ever get the economics right," one of the Journal articles noted, adding that "Most delivery orders remain unprofitable."

Like competitors of Amazon, restaurant and grocery chains are willing to absorb the losses for now, worried they will miss the ecommerce wave and jeopardize their market positions. They also hope the cost-sell dynamics will change over time.

Consumers in major metro markets are the most frequent users of food delivery, but the trend is also gaining traction in many suburbs and smaller urban markets, putting more pressure on the stores and restaurants in these less dense areas.

However, investment firm William Blair estimates sales just of on-line restaurant delivery will grow to $62 billion in 2022 from about $25 billion today - so the chains and even mom and pops just have to be there.

"Customers have raised their expectations. The whole framework has changed," Frans Muller, CEO of grocery chain Royal Ahold Delhaize told the Journal. Ahold owns the Peapod grocery delivery service, which it has said is only profitable in a handful of markets after operating for many years now.

Earlier this year, Kroger reported profits were down in its recently ended fiscal quarter, citing huge investments in the hundreds of millions of dollar range in its ecommerce operations. Its shares fell a sharp 10% that day on the news.

Grocers of course have special challenges, as most food must be packaged carefully, often segregated from other items, and sent in refrigerated trucks, all of which add to costs.

And the average on-line grocery order contains dozens of items, which often have different temperature and handling requirements.

Restaurants also need to pack orders in special containers, may need temperature controlled storage in delivery trucks, and must deliver within a short windows to keep the meals fresh for consumers.

Unlike most restaurants, which use third-party delivery companies such Grubhub, DoorDash, and Uber Eats, Panera does its own deliveries in most markets. But that capability came at a hefty price. The chain spent six years and more than $100 million to develop the technology to process its own on-line orders.

The Journal says the investment cut into profits for three years, but began to pay for itself in 2016.

Further complicating matters is that many of the delivery services actually take the customer orders for restaurant meal delivery from their own web or mobile sites - taking some of that margin. Other chains are handling the order-taking through their apps but outsourcing the actual delivery to third-party services, often at a loss.

Another article in the series noted some of the oddities of grocery delivery, especially around out-of-stocks and resulting order substitutions. One customer interviewed ordered broccoli and received kale instead.

That was bad enough, but another ordered regular coffee and – shudders – somehow wound up with decaf.

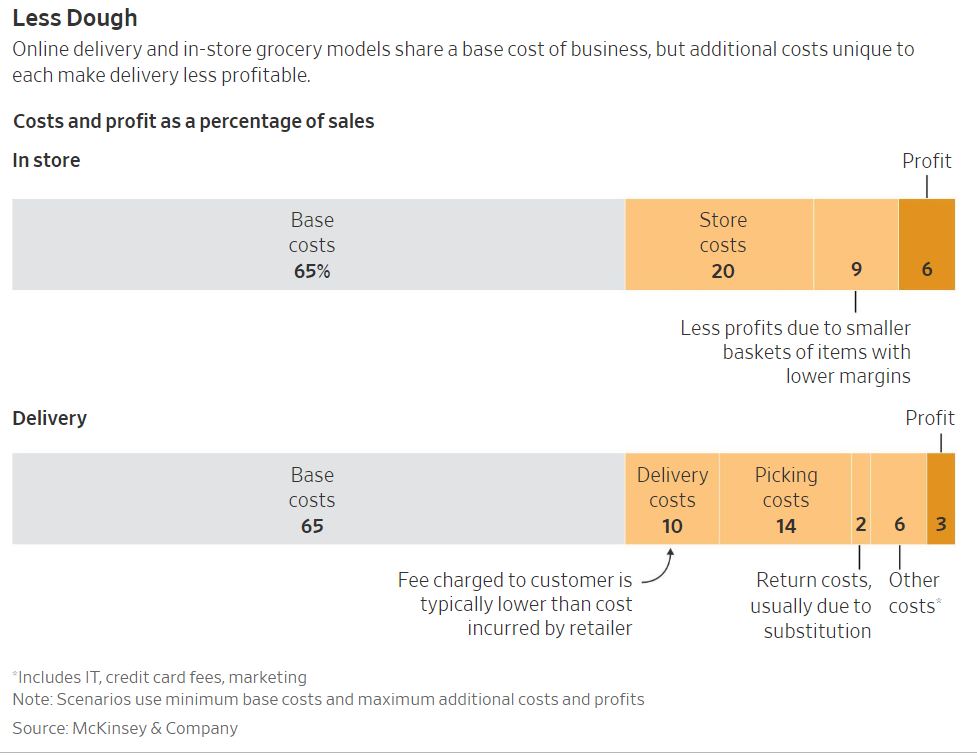

Another article took a look at costs and margin for grocers when comparing the numbers between traditional in-store sales and those for ecommerce orders with home delivery, as shown in the graphic below.

Source: Wall Sreet Journal

As can be seen, both types of orders begin with food costs of 65 cents out of a dollar of sales. In-store sales have total store overhead costs of 20% of sales, versus a combined 24% for in-store picking/packing and delivery costs.

That cost advantage for stores sales is somewhat offset (add in 9%) for the smaller "basket" on average for store sales, but delivery sales have higher costs for returns (2%) as well as 6% higher costs for other areas such as credit card fees (assume many in-store shoppers must still use cash,) and IT and marketing expense.

That leaves in-store sales providing a profit of six cents on the dollar, versus half - just three cents - for home delivery orders.

But again, on-line is where the growth is, and I expect these costs to change over time (e.g., picking may get more efficient, IT costs should come down). On the other hand, delivery costs are likely to head higher, in my view.

But perhaps there is an answer to all this: autonomous mobile robots.

Fast-food chains and grocery stores are teaming with big car companies and tiny startups to test the idea of autonomously shuttling food to customers. During tests in Miami, Michigan and Las Vegas, Domino delivered more than 1,000 pizzas in Ford sedans covered in signs that read "self-driving delivery test vehicle." Venture-backed startups have dispatched a few hundred smaller robots in places such as Berkeley, Calif., to navigate around pedestrians and deliver burritos or groceries to customers' doorsteps.

We've reported on the development and testing of AMRs from companies such as Starship Technologies, a sidewalk robot start-up, for some time. Starship CEO Lex Baker is naturally bullish on the small form factor solution. "To have a 2-ton vehicle driving 3 miles to deliver a burrito to someone is not the most practical thing for the world," he says.

Food companies are betting that such automation can reduce delivery costs by as much as 40%, according to McKinsey & Co., while also helping ease a shortage of delivery drivers.

But door-to-door robot service - a solution to what McKinsey calls the "last-10-yard" problem - is still a decade out, insider say.

I say longer.

Walmart is trying of course to get in the game, but is finding it's not easy. It mainly relies on a patchwork of independent companies to expand its delivery services as quickly, broadly and cheaply as possible. However, for drivers at those delivery firms, the economics of shuttling Walmart's and other grocers' orders don't always make sense.

For consumers, it's all about saving time, amid – perhaps surprisingly - a trend towards more meals eaten at home, which started in the Great Recession but has not abated, spurred on, it seems, even from other trends like video streaming services. But home delivery eliminates the need to cook while staying in-house – and now there are a lot more options than pizza. The wine and beer at home is also a lot cheaper.

What is this world going to look like in 20 or even 10 years?

I think it's clear that with current approaches, delivery costs are going to go up, which will put some damper on the food delivery party. But if autonomous vehicles or drones can cut those costs substantially, then the floodgates may really open.

What's your take on food and grocery deliveries? Will tech eventually drive down costs? Let us know your thought at the Feedback section below.

Your Comments/Feedback

|